An Artist Sends Smoke Signals from an Apartment in Brooklyn

“I realized my art is just as valuable now.”

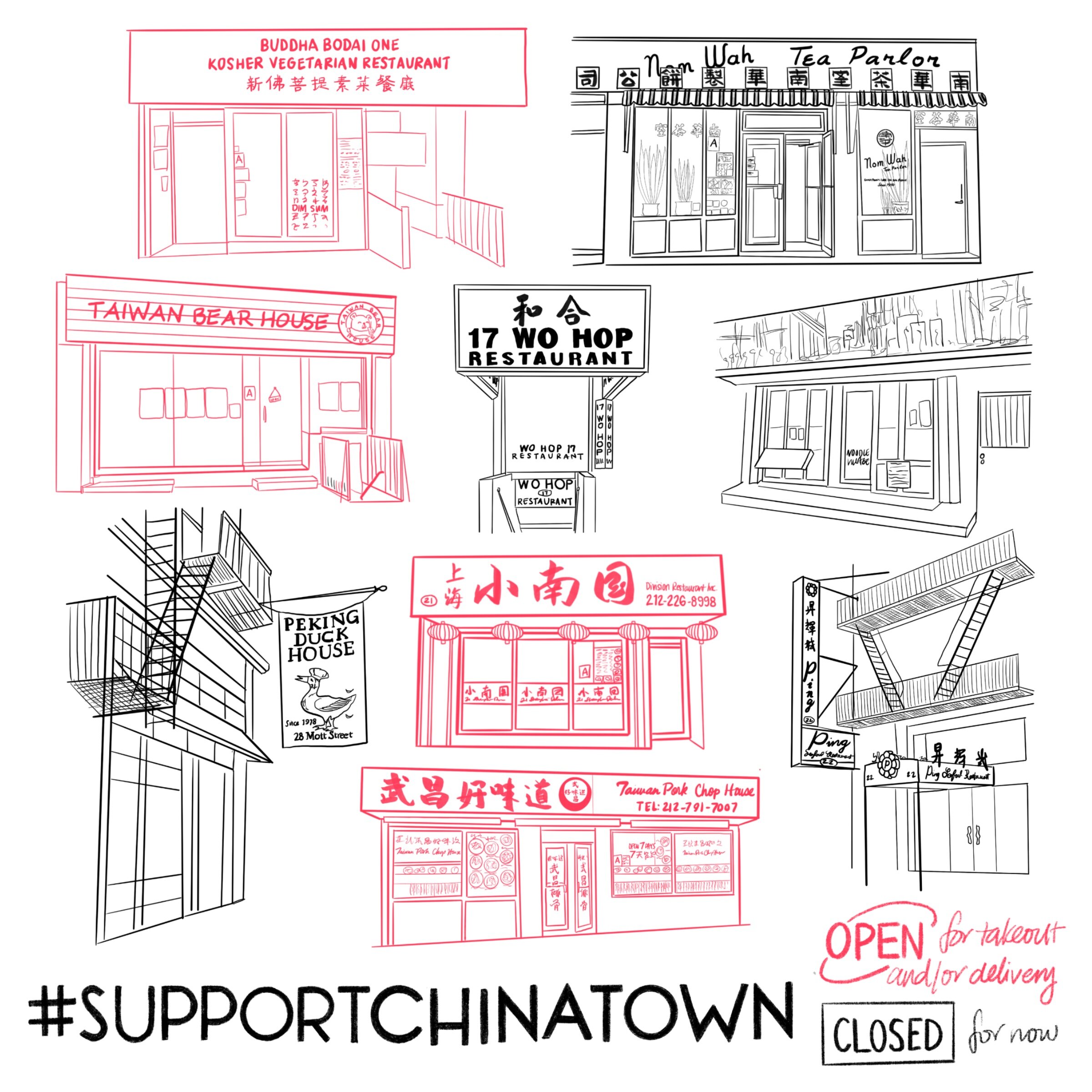

The 31-year-old illustrator Felicia Liang uses her art to keep New Yorkers updated with the current state of Chinatown. Art courtesy of Felicia Liang

On a normal day, the Taiwanese-American artist Felicia Liang could easily take the train from her home in Crown Heights to eat tsuabing in Chinatown to celebrate the early approach of summer. Maybe then the biggest hurdle between her and an afternoon at Hong Kong Supermarket would be entering the subway station to see the 2 line isn’t running, or the D has been delayed, instead of doing the limbo to enter the store. But, while the MTA operates for essential travel only, Liang chooses to stay safe inside her Brooklyn apartment with her colored pencils, Moleskine journals, an unfortunate lack of Asian groceries—and a recipe to help preserve Manhattan’s Chinatown.

“I miss the food. I miss having boba options every block. I miss the bustle. I miss speaking rudimentary Mandarin to street vendors when pointing at produce I want to purchase,” the 31-year-old mused. So, last month Liang started to do what creatives tend to do in times of trouble: make art to make an impact.

Since March 21, the artist—who typically uses her work to “connect with others and highlight cultures and ideas not commonly found in mainstream media”—has posted nearly 20 times to inform the public of its available food options through her fine-line illustrations of Chinatown restaurants, cafes and grocers still open for business during the state-mandated shutdown. Liang debuted her new project with nine minimalist illustrations outlining the fluctuating statuses of local restaurants like Wo Hop, The Original Buddha Bodai, Shanghai 21, Nom Wah Tea Parlor, Noodle Village, Peking Duck House and more with a call to #SupportChinatown through takeout and delivery.

“I thought it seemed like a silly project at first and wondered what the point would be if many of these places are closed,” she admitted. “There were a ton of relief efforts underway, and I could only donate in small increments, but I realized my art is just as valuable [as money] now.” Using the software Procreate, Liang lays out the businesses on the page in either red—to signify a brick and mortar is still in business—or black—to note when it temporarily closes.

What may seem like a simple color code has been appropriately called an “artistic public service announcement,” she said, as the coronavirus crisis keeps many New Yorkers confined to their homes—unable to investigate the situation on foot—and business owners without social media are left struggling to communicate their current conditions themselves. “I couldn’t have asked for higher praise,” Liang said of the PSA classification. “I wanted to shine a light on a community that means so much to me,” she said. “Drawing has always been therapeutic for me during difficult situations, and art has an incredible ability to heal, to uplift, to tell stories and to build community.”

Liang sources the crucial information for her illustrations from resources like Explore Chinatown and Think!Chinatown in addition to locals commenting real-time updates—usually accompanied by an empathetic set of emojis—with her that she then incorporates into the captions. “It's so important to do what we can to help support these businesses, especially with the current climate of misunderstanding and hate,” Alimama Tea echoed Liang early on. The Kopitiam account agreed, commenting ecstatically on a post featuring the front of their restaurant facing East Broadway. Some in the area, such as Yaya Tea, even shared the project after their business switched from “red” to “black.”

Liang considers the ongoing endeavor a community project. “Small businesses and creatives have been hit hard by the pandemic so social media interaction has been a way for us to support one another,” she said. “I’ve been trying to use my art to build community and try to foster some sense of togetherness.”

Pre-pandemic, Liang had planned to draw her favorite spots in New York to celebrate her 10 years in the city, which, come August 2020, will mark the longest time she has lived in a single place. The plan shifted to focus on Chinatown when she saw reports of xenophobia before the first case of coronavirus hit the United States. “I remember how empty it was weeks before the lockdown—due to racism—and it made me sad and angry at the same time,” she said. “My last night out before having to stay at home was in Chinatown, and I was worried about how many of these businesses will be standing at the end of this.” (The former Pearl River Mart artist in residence did a deep dive of Manhattan’s Chinatown in 2016 while completing a previous art project, #100DAYSIANS, which she called a “transformative time” for her as both an artist and Taiwanese American.)

When Liang first heard of coronavirus in late December—then again in January when her doctor said “it might just be another bad flu”—she had no idea it would get this bad. “We both didn’t know enough then and it revealed just how untimely our own government had informed the public.” She said her friends living in Europe and family in Taiwan have been “shocked” by what she describes as the “broken” American healthcare system and discrimination against Asian Americans, and they worry for Liang and her brother, who also lives in New York.

“The news stories you hear and videos you see about the hate crimes and harassment against Asian Americans and Asians around the world are painful and horrifying. As the numbers of infections and deaths rise, it’s stoking even more fear, stigma, and prejudice, and it’s happening everywhere—even in the most diverse cities in America,” she said. “Now I can’t help but walk around outside without feeling a little suspicious.”

Liang looks at the shutdown as an opportunity to build solidarity. “We need to speak up when we see something—only if it’s safe to do so—and stop the spread of misinformation. Report hate crimes to help track these incidents and demand better action to protect our community at the state and federal level. Stay updated with the news and on the latest around you. Stay informed and stay vigilant, and talk to your friends and community about this, too—it’s happening to more people than you think.” She suggests others can show their own support of Chinatown and Asian-owned businesses by contributing to ongoing relief efforts, ordering takeout or delivery, and sharing relevant stories digitally, but Liang believes the government needs to do its part as well. “The next aid bill needs to help all restaurants—not just large chains. It needs to ensure that restaurants can survive (rent relief, access to all applicable loans, etc.) even though many are closed for now, and that restaurants open for takeout and delivery can safely operate,” she said. “Workers who have lost their jobs or need to shelter in place need to be taken care of—and relief needs to include undocumented workers.”

While social-distancing-as-the-norm moves into the month of May, Liang holds onto hope for widespread testing and a vaccine, multiple meals with friends and the chance to walk the streets of Chinatown again. “I love the history of Chinatown—and knowing how tight knit and active the community is in supporting one another and its ability to quickly adapt during the toughest of times,” she said. “I remember an old article in New York Magazine about ‘how Chinatown has stayed Chinatown’ and there was a quote about how Chinatown from the start is a place where immigrants reinvent themselves to survive, which beautifully encapsulates why it is so unique, so resilient—and so beloved.”

As for the woman herself who hopes to return to the part of lower Manhattan that she is—in her own way—helping maintain, Liang currently spends her quarantine time making to-do lists (relatably categorizing items by “should do” and “want to do”), collaborating on other initiatives (she recently designed these limited-edition Jing Fong T-shirts and totes), working on personal projects (and selling her dim sum prints), looking for gigs (she is presently open for commissions), applying for relief efforts for creatives, taking classes online, working out, chatting with friends and, perhaps most importantly, as she does not fail to mention—eating and sleeping.

Liang said she is taking it all “day by day,” and ultimately considers herself lucky to be where she is in this moment—complete with the mask her mother mailed her, which came via her mother’s friends (in another example of an innovative supply chain). “I live alone, and while it’s been difficult not being around people, it’s given me time to focus on my business and my project ideas. I saved up when I knew I was going to quit my job [as a product manager in October], and I’m thankful to have food, a safe place to stay—and Medicaid.”

Her first stop when the city turns back to red? An Asian supermarket for groceries, of course.